6 Con: A Language of Conditions

6.1 Multiple types of values

Until now our language produced only one kinds of values: integers. While useful for calculating arithmetic expressions, it is quite limiting. Let’s first address it by introducing boolean values into the language. We will call our new language Con. The two values we will add are #t for true and #f for false. These mirror Racket’s boolean values. Adding boolean values is pointless if our language does not allow us to operate over such values. So we will add some operations if, <=, zero?, and and. We’ll describe these operations in detail.

6.2 Syntax

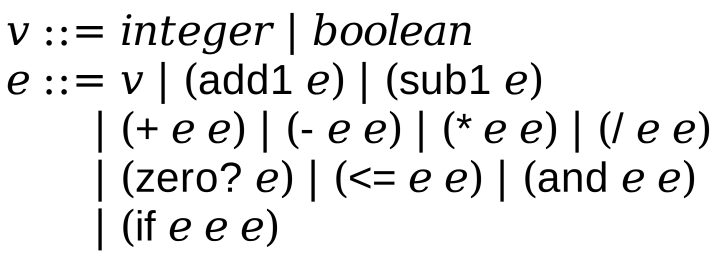

Con extends Arithmetic: Computing Numbers by these operations we described above. It contains #lang racket followed by a single expression. Our expressions have integers, booleans, and additional operation like and, if, zero? and so on. The grammar of concrete expression is:

Thus few examples of valid Con programs are:

#lang racket (+ 42 (sub1 34))

#lang racket (zero? (- 5 (sub1 6)))

#lang racket (if (zero? 0) (add1 5) (sub1 5))

6.3 Meaning of Con Programs

We will define the meaning of Con programs in natural language. We only define the meaning for the new parts of the language here, the old parts of language stays same.

The meaning of literal values is just the value itself;

The meaning of zero? is true if the subexpression is 0 or false otherwise;

The meaning of and is false if the first subexpression is false, otherwise it is the result of the second subexpression;

The meaning of <= is a test for if the first subexpression is smaller than or equal to the second subexpression;

Finally, (if e1 e2 e3) means e3 if e1 means false, or e2 otherwise.

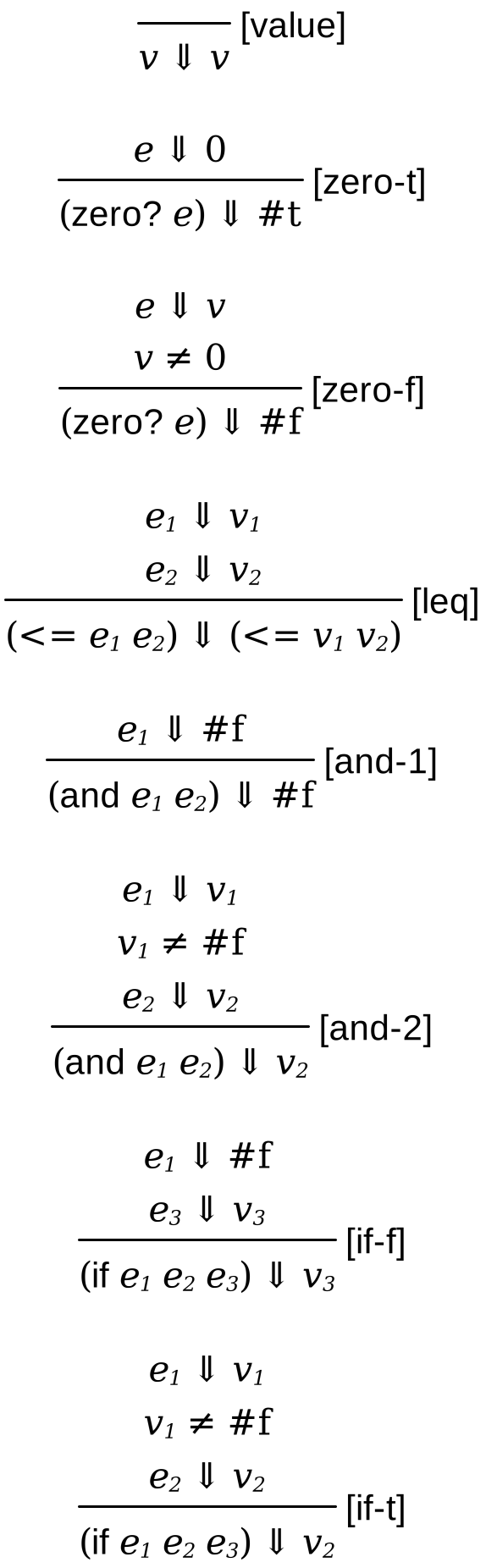

We define the operational semantics as before in terms of the  relation.

relation.

Values in our language form the base case in our inductive relation. The value rule shows the meaning for integers, #t, and #f respectively.

(zero? e) has two cases. For all expressions e zero-t rule means #t if e means {0}. Alternatively, it means #f (rule zero-f) if e is non-zero.

For all expressions e1 and e2, (and e1 e2)  #f

is in the relation if e1

#f

is in the relation if e1  #f. Otherwise, the relation has

the same meaning as e2. Note, how a definition like this works for both

booleans and integers. (and #t #t) is #t, (and #f #t) is

#f, (and 4 5) is 5, and so on.

#f. Otherwise, the relation has

the same meaning as e2. Note, how a definition like this works for both

booleans and integers. (and #t #t) is #t, (and #f #t) is

#f, (and 4 5) is 5, and so on.

For all expressions e1 and e2, (<= e1 e2)  #t

if e1 means a value less than the meaning of e2.

#t

if e1 means a value less than the meaning of e2.

For all expressions e1, e2, and e3, (if e1 e2 e3)  e2 is in the relation if e1 means some non-false value.

Otherwise (if e1 e2 e3)

e2 is in the relation if e1 means some non-false value.

Otherwise (if e1 e2 e3)  e3 is in the relation if e1 means false.

e3 is in the relation if e1 means false.

6.4 Interpreter for Con

We can now translate these operational semantics rules to the interpreter:

#lang racket (require rackunit) (provide interp) ;; Expr -> Value ;; Interpret given expression (define (interp e) (match e [(? integer?) e] [(? boolean?) e] [`(add1 ,e) (+ (interp e) 1)] [`(sub1 ,e) (- (interp e) 1)] [`(+ ,e1 ,e2) (+ (interp e1) (interp e2))] [`(- ,e1 ,e2) (- (interp e1) (interp e2))] [`(* ,e1 ,e2) (* (interp e1) (interp e2))] [`(/ ,e1 ,e2) (quotient (interp e1) (interp e2))] [`(zero? ,e) (interp-zero? e)] [`(and ,e1 ,e2) (interp-and e1 e2)] [`(<= ,e1 ,e2) (<= (interp e1) (interp e2))] [`(if ,e1 ,e2 ,e3) (interp-if e1 e2 e3)])) (define (interp-zero? e) (match (interp e) [0 #t] [_ #f])) (define (interp-and e1 e2) (match (interp e1) [#f #f] [_ (interp e2)])) (define (interp-if e1 e2 e3) (match (interp e1) [#f (interp e3)] [_ (interp e2)]))

> (interp '(+ 42 (sub1 34))) 75

> (interp '(zero? (- 5 (sub1 6)))) #t

> (interp '(if (zero? 0) (add1 5) (sub1 5))) 6

You can use builtin Racket functions like and, zero? instead of writing pattern matches. However, you have to ensure that the semantics of such builtin functions align with the semantics of the target language you are implementing. The question then is: are the semantics of and and zero? in our language, Con, the same as Racket?

We can find a one-to-one correspondence between what the interpreter for Con

does and the semantics of the language. Where ever  shows up in the

premise of an operational semantics, it results in recursively calling our

interpreter (interp ...). When we have separate rules that may give

different meaning to the same language construct we use a pattern match and

return the right value.

shows up in the

premise of an operational semantics, it results in recursively calling our

interpreter (interp ...). When we have separate rules that may give

different meaning to the same language construct we use a pattern match and

return the right value.

6.5 Correctness

We can turn the above examples into automatic test cases:

> (check-eqv? (interp '(+ 42 (sub1 34))) 75) > (check-eqv? (interp '(zero? (- 5 (sub1 6)))) #t) > (check-eqv? (interp '(if (zero? 0) (add1 5) (sub1 5))) 6)

However, unlike Arithmetic it is easy for us to write malformed programs, i.e., programs that do not mean anything. In other words the meaning of such programs are undefined in our semantics and would most likely crash our interpreter with unexpected error messages or produce unexpected results.

Here are a couple of programs in Con that are valid according to the syntax, but do not mean anything:

> (interp '(add1 #t)) +: contract violation

expected: number?

given: #t

> (interp '(<= #t 7)) <=: contract violation

expected: real?

given: #t

Our interpreter right now does not handle errors gracefully and crashes with errors directly from the underlying Racket runtime.